"La Rose de Jéricho" by Aurélia Zahedi

For thousands of years, this mythical plant concealed in the folds of the desert has stirred the imagination of those who encounter it or look out for its traces. Although humble and modest, nestling low to the ground, the plant is associated with resurrection and the sacred. It is said to be immortal, nomadic, a healer and women’s ally. Aurélia Zahedi set off in its footsteps in 2016 and has continued her quest ever since, trying to determine if this plant is indeed intrinsically connected to Jericho, the city whose name it bears. Travelling across the Sahra’ charq al-Quds in Palestine (the desert to the east of Jerusalem) alongside the Bedouins of Nabi Moussa, Aurélia Zahedi listens to the silence and embraces the diversity of perspectives, composing a protean narrative made up of several voices.

Three botanical species share the name of Rose of Jericho. But does a genuine one actually exist? It is said that this revivifying plant emerged in the cradle of the world’s oldest city (and the one with lowest elevation). Located near the Jordan River, Jericho boasts a multitude of canals and a wealth of different cultures and yet the eponymous Rose grows amidst the sand and rocks, only blooming in contact with the rare and precious rain that makes the desert blossom. This plant is the eyes and the ears of the desert, its subtle pulse, and the repository of stories threatened with disappearance. When awakened from its dormancy by the rain, its dry, curled branches unfurl, its leaves turn greenand its protected seeds are dispersed. At the heart of disputed borders, the Rose becomes a storyteller, sharing the turbulence of a land torn apart by human madness. Its shadow reveals the moral, physical and symbolic suffering of an entire population as we are invited, through poetry, to take the measure of a stifled identity.

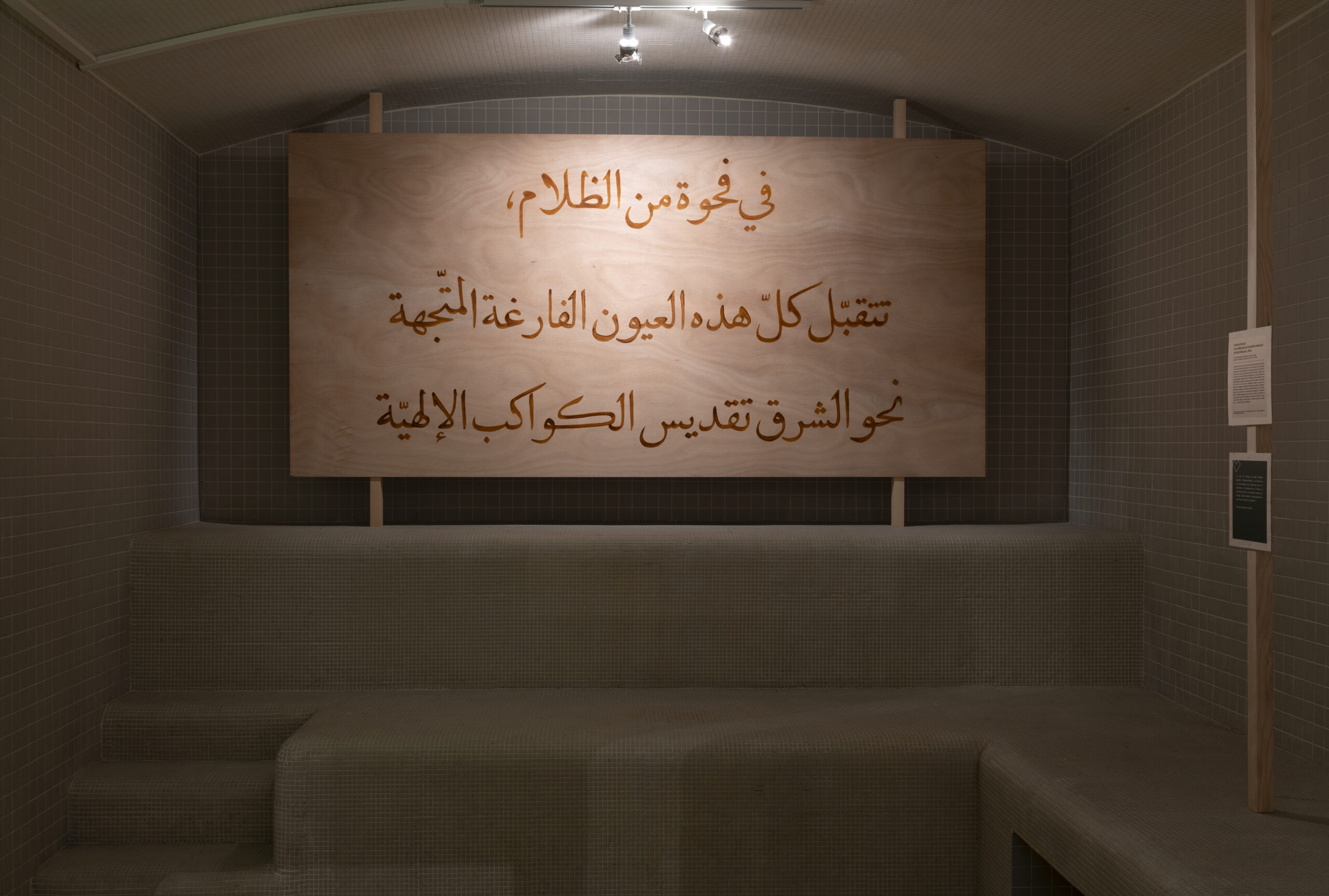

In the hammam of the ICI – Institut des Cultures d’Islam, Aurélia Zahedi’s Roses of Jericho come to life, distilling their testimonies through occasional ceremonies and a selection of works produced over the last five years, some of which have never been exhibited. Navigating from the earth to the sky, and from the scorching sun of the day to the guardians stars of the night, the exhibition points to the connections between the plant, its territory and its landscapes. It reminds us of the power of the imaginary in contexts of constraint or even inner exile, and at a time when beliefs, orality and memory oscillate between emergence and obliteration.

Clelia Coussonnet

Independant curator, researcher, writer and editor

Aurélia Zahedi

Phrases, in situ

Aurélia Zahedi’s practice is rooted in a distinctive relationship with language and writing, in fruitful dialogue with images. Her quest for the Rose of Jericho started with a lengthy textual research, before continuing in the field in Palestinefrom 2018.

Her visual production and her Rose Ceremonies are informed by the words, songs, poetry and stories she writes or receives. Calligraphy, in collaboration with a master miniaturist, also plays an important part in her work, as illustrated by her series Portrait de Bédouin and La prière de Nesrine. Iconography and written words are complementary, incentives to the imagination and to travel. In resonance, the exhibition features calligraphic texts punctuating the space like mirages in the desert.

Aurélia Zahedi

Herbier de l’ancien cimetière musulman de Jéricho, 2019

Although the name “Rose of Jericho” seems to come from the Crusaders (who brought specimens back to Europe), the plant is as closely connected to Islam as it is to Christianity. One of its names in Arabic is Kaff Maryam (the palm ofMary/Maryam) because it is said that the mother of Jesus/’Issa touched the Rose while laying her washing on the ground to dry.

In 2018, Aurélia Zahedi invited the agronomist and market gardener Marie Rue to accompany her on a research trip to Palestine. Echoing the myth of the Rose’simmortality, they imagined it carried by the winds through cemeteries where, as a tenacious historical memory, the plant gathers testimonies of the dead for the living. The weeds they collected in the old Muslim cemetery of Jericho/Ariha are suspended in a glass sculpture alongside their names in Latin and Arabic. The sculpture is shaped after a Muslim grave, with its characteristic rounded headstone reminiscent of the Mecca/Makka’s dome.

Aurélia Zahedi

Portrait de Bédouin – Saqer. Portrait de Bédouin – Inad. Portrait de Bédouin – Naif. Portrait de Bédouin – Moussa, 2023

On her first trip to Palestine, Aurélia Zahedi met Saqer S.H. Alkawazba, a member of the Bedouin community of Nabi Musa with whom she set out to share the many stories of the Rose of Jericho. He gazes out from his portraitcalling on us to be witnesses, as do the other fellow travellers with whom the artist collectively imagines the story of the plant. Inspired by the Persian miniatures from the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925), which combine portraits of nobles or rulers with calligraphy of their name and title, these paintings pay tribute to the Bedouins and their knowledge of the desert. Instead of miniatures, Zahedi has chosen to paint life-size representations. The shepherds’ dignified faces blend into a desert rich in textures and nuances, thereby evoking the gradual disappearance of this population from its territory. As this nomadic population is forced to either settle down or move away, the transmission of their knowledge and the preservation of their way of life are under threat.

Aurélia Zahedi

Vase lacrymatoire, 2023

In ancient Rome, it was customary to bury in the graves lacrimatory vessels which were said to collect the tears of mourners. Adopting their delicate shape, Aurélia Zahedi’s blown glass vase seems to contain the tears of the Bedouinsinstead. The borders, checkpoints and division of their land, which make it difficult to get supplies to their herds, as well as the regular destruction of their camps by the Israeli army and their forced displacement to the outskirts of urban areas, risk cutting the Bedouins from the desert in which they have been living for centuries, and accentuating the generational divide. In the past, pastoralism structured their lives, but, in recent years, their freedom of movement has been restricted or confined to areas where tourists see a stereotypical image of their life.

The vase could also refer to the increasing scarcity of water in Palestine. This precious resource is captured and diverted particularly for the benefit of the Israeli settlements.

Aurélia Zahedi

La Rose de Jéricho, 2023

This video, seemingly suspended in time, irrevocably links the history and memories of the Rose of Jericho to those of the Bedouins, the desert and those of Palestine more broadly. From one mirage to another, we follow a Bedouin teenager on a donkey, modern-day Virgin Mary, along trails of an impossible cartography. Oscillating between reality and fiction, this spiritual and secular story (that verges on the political) shows the everyday life of these nomads and their many animals in the desert near the sanctuary of Nabi Musa/Prophet Moses, where the latter is said to be buried. In this poem narrated by a Palestinian voice, the constant wandering through a landscape surrounded by visible and invisible borders is strongly evocative of “being condemned to exile in one’s own land”. While the video highlights the multiple griefs at work, it also celebrates the life that pulses in the desert.

Aurélia Zahedi

Réveil de la Rose de Jéricho, série, 2018

The Rose of Jericho sketches out its own opening in this series of Indian ink drawings, symbolically displayed in the hammam’s showers. In the absence of water, the plant can remain dormant for many years. A drop of rain is all it takes for it to awaken, unfolding its branches and dispersing its seeds to ensure the species persists. Thanks to its many “resurrections”, it is considered to be a sacred, eternal plant.

For these drawings, Aurélia Zahedi replaces water by ink to show the vigorous manner in which the plant unfurls, impalpably distilling its memories of the desert on the paper. Each work in the ensemble has its own story to tell. The Rose is a witness; her eyes sharing what the Bedouin can no longer evoke of this land that is slipping away from them.

Aurélia Zahedi

La prière de Nesrine, série, 2023

Nesrine, a woman in the Bedouin family visited by Aurélia Zahedi, prays at night as if to absolve the sins of the day past and the day to come. The three paintings in this series draw inspiration from Persian miniatures from the Safavid dynasty (1501-1736), both in terms of aesthetics and in their technical use of gold leaf and of a typical margin, tach‘ir, decorated with blue flowers. A poem by the artist calligraphed on each drawing suggests the repetition of Nesrine’s prayer by asking: “Could the sky wash the earth of our inhumanity?” These works address the violent context of Jericho/Ariha and its surrounding desert, as well as the fragile existence of Bedouin and Palestinian populations living in constrained and occupied territories.

The presence of Nesrine also underlines the strong connection between the Rose and women because the plant is a vernacular remedy linked to childbirth, menstruation and fertility.

Aurélia Zahedi

Les veilleuses du cimetière bédouin de Nabi Moussa, série, 2023

© Tanguy Beurdeley

The elements (water, earth, fire, air) that link the Rose of Jericho to its desert environment are evoked throughout the exhibition. They accompany a journey from the depths of its territory (with the sculpture-tomb of the herbarium) to the skies above in these last three photographs. The celestial vault unites disjointed geographies and uncrossable borders. Its stars watch, soothing the troubles of the living, in a context of conflict where death is always at the door. Since time immemorial, the nomadic Bedouins have always returned their dead to the desert, trusting the stars above the cemetery of Nabi Musa to watch over them. Night also provides a place to hide and opens up other imaginary worlds. This infinite, indeterminate space suggests that the myth of the Rose of Jericho is not part of any absolute truth. As the old tales of the region go: “Kan ya ma kan”, which can be translated as “Once upon a time, there was, and there wasn’t”. The Rose is not, and is…

Aurélia Zahedi

Reliques de la Rose de Jéricho, 2018

Terre de l’Asteriscus pygmaeus, Eau de la mer Morte, Terre de l’Asteriscus pygmaeus, Terre de l’Anastatica hierochuntica

Blown glass sculpture, desert earth, 4.5 x 19 cm ; Glass sculpture, water and salt from the Dead Sea, 24 x 5 x 7 cm ; Blown glass sculptures, desert earth, 7 x 7 cm ; 12 x 10 cm. © Marc Domage

The story goes that the Rose of Jericho was born from the footprints of Mary/Maryam as she fled to Egypt. Inspired by this, Aurélia Zahedi collected a little water or a handful of earth in the different places where she found this rare plant, easily confused with the colour of stones. Just like the fragments of bodies or objects of saints that are worshipped, Aurélia Zahedi considers this soil – sacred to the three monotheisms – to be a relic in its own right. In a context of disappearance and obliteration, it subsists, conveying memories and stories. Like other works in the exhibition, these sculptures are made of glass, a material made from sand and fire that evokes the land across which the Rose travels. Each sculpture has a different shape, reflecting the infinite diversity of the desert beneath its apparent uniformity. The reliquaries become clues that point to features of the landscape – mountains, shores and paths – in which a Rose has been glimpsed.

Aurélia Zahedi

PATIENS QUIA AETERNA, 2018 ; En attente de boire la lune, 2023 ; Résurrection, 2023

The first Rose Ceremony took place in 2018 when Saqer S. H. Alkawazba, with whom Aurélia Zahedi roams the desert in search of the plant, found one that he watered and gave her while telling a story. Since then, alone or in the company of her Bedouin associate, Aurélia Zahedi invites the public to join her while she reproduces this gesture of opening in a performance that combines poetry, song, spoken word, improvisation and recitation.

The ceremonial glass chests presented in the exhibition are distinctively shaped glass sculptures, each dedicated to one of the three botanical species that are referred to by the name Rose of Jericho. They pay tribute to this unique and precious plant that opens doors to the imagination and allows protean narratives to exist in a land in conflict. The chest En attente de boire la lune, whose shape is inspired by cults devoted to lunar divinities by the city of Jericho/Ariha in ancient times, will be activated during various Rose Ceremonies (see the ICI “Events” schedule).

In everyday language, three plants are known as Rose of Jericho, a mythical name with a strong aura, but rather imprecise and source of scientific quarrels. In botany, they are known as Anastatica hierochuntica L., Asteriscus pygmaeus (DC.) Coss. & Durieuand Selaginella lepidophylla (Hook. & Grev.) Spring. The first two can be found in Palestine, whereas the third is native to the Chihuahuan Desert in Mexico.

This term bears witness to the way in which, over centuries, obsession with botanical categorisation and taxonomy merged with legendary stories about fantasised plants. Indeed, several botanists claimed to have found the true Rose of Jericho, trying to give it their own name in the form of a Latin taxon.